Snakebites pose a major public health challenge, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. Every year, millions suffer from venomous snakebites, leading to over 100,000 deaths and countless cases of amputations or permanent disabilities. Snake venom contains potent toxins that can cause paralysis, tissue destruction, and internal bleeding, making rapid and effective treatment essential.

Fortunately, recent advancements in science and medicine are paving the way for more effective treatments. In this blog, we’ll explore how snake venom affects the body, current treatment methods, and groundbreaking innovations that are set to revolutionize antivenom therapy

Global Impact of Snakebites

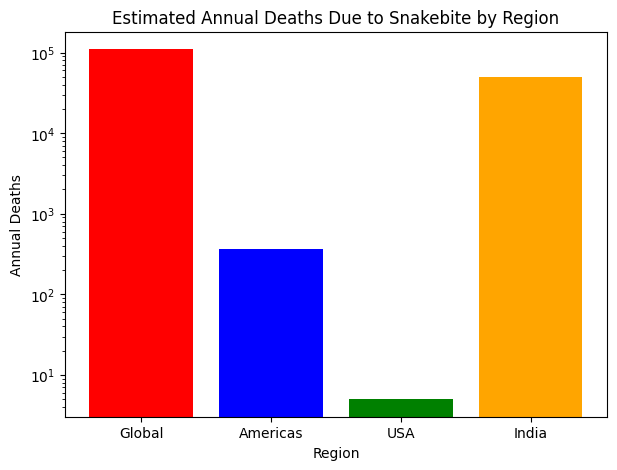

Snakebites are a significant global health concern, particularly in rural and tropical regions. Each year, an estimated 5.4 million people worldwide are bitten by snakes, leading to approximately 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenoming. Tragically, these bites result in around 81,410 to 137,880 deaths annually, with about three times as many individuals suffering amputations and other permanent disabilities.

The impact of snakebites varies by region, with the Americas reporting around 57,500 cases annually, leading to nearly 370 deaths, while the United States sees 7,000 to 8,000 bites, resulting in about five fatalities. India bears a significant burden, though exact figures are difficult to determine due to underreporting. Many snakebite incidents, especially in rural areas, go unreported, making the actual numbers likely higher. Improving data collection, raising awareness, and enhancing access to medical care are essential steps in reducing the global impact of snakebites.

Understanding Snake Venom and Its Effects

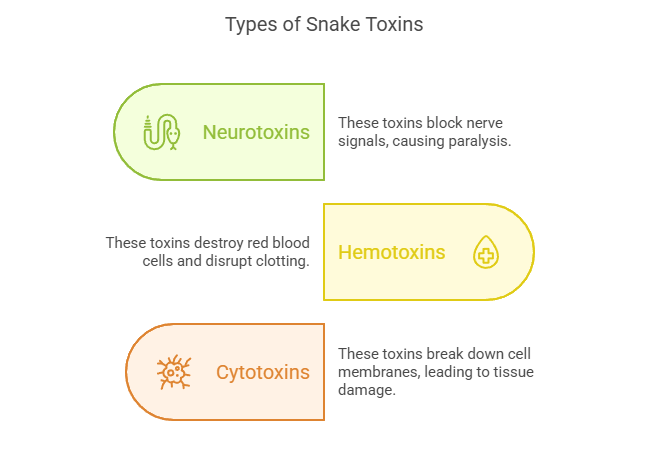

Snake venom is a complex cocktail of proteins, enzymes, and peptides that vary depending on the species. These toxins target specific systems in the body, such as the nervous system, blood coagulation pathways, or muscle tissues. For example:

- Neurotoxins : Found in cobras and kraits, these toxins block nerve signals, leading to paralysis and respiratory failure.

- Hemotoxins : Common in vipers, these toxins destroy red blood cells and disrupt blood clotting mechanisms, causing hemorrhage and organ damage.

- Cytotoxins : Present in some rattlesnakes and other pit vipers, these toxins break down cell membranes, leading to tissue necrosis.

The diversity of snake venoms makes it challenging to develop universal treatments. Traditional antivenoms are often species-specific, requiring precise identification of the snake involved a task that isn’t always possible in emergencies.

Current Treatments: Antivenoms and Their Limitations

The primary treatment for snakebite envenomation is antivenom, a life-saving medication composed of antibodies derived from immunized animals, typically horses or sheep. These animals are exposed to small, controlled doses of snake venom, prompting their immune systems to produce antibodies. These antibodies are then harvested, purified, and formulated into antivenom. When administered to a snakebite victim, the antivenom works by binding to the venom’s toxic components, neutralizing them before they cause severe physiological damage.

Limitations of Conventional Antivenoms

Despite their effectiveness, traditional antivenoms have several limitations:

Species-Specificity – Most antivenoms are designed to neutralize venom from specific snake species or closely related groups. This poses a significant challenge in regions where multiple venomous species coexist, as medical professionals may struggle to identify the exact snake responsible for the bite. In cases of misidentification or unknown bites, the wrong antivenom may be administered, leading to ineffective treatment. While some broad-spectrum antivenoms exist, they are often less effective than species-specific ones and may require higher doses, increasing the risk of side effects

Adverse Reactions – Because conventional antivenoms are derived from the plasma of immunized animals, such as horses or sheep, they contain foreign proteins that can trigger immune system responses in humans. Some patients develop immediate allergic reactions, ranging from mild itching and hives to severe anaphylaxis, which can be life-threatening. Others may experience serum sickness, a delayed immune response that can cause fever, joint pain, and skin rashes days or weeks after treatment. Due to these risks, medical personnel must closely monitor patients and, in some cases, administer additional medications like antihistamines or corticosteroids to manage side effects.

Cold Chain Dependency – Most antivenoms require constant refrigeration (typically between 2°C and 8°C) to maintain their stability and effectiveness. This creates major logistical challenges in rural and underdeveloped areas, where electricity and reliable cold storage may be scarce. In tropical regions with high temperatures, improper storage can lead to the degradation of antivenom, rendering it ineffective when needed. Additionally, transporting antivenom to remote locations is difficult, as it requires specialized equipment and infrastructure, which are often lacking in snakebite-prone communities.

High Cost and Limited Access – The production of antivenom is a complex, time-consuming, and expensive process. It involves raising venomous snakes for venom extraction, immunizing animals, purifying antibodies, and ensuring rigorous quality control. These steps drive up costs, making antivenom unaffordable for many low-income communities, where snakebite cases are most prevalent. In some regions, limited government funding and healthcare infrastructure further restrict access to life-saving treatment, forcing patients to travel long distances to obtain antivenom often at great personal and financial cost..

These challenges highlight the urgent need for innovative treatments, such as synthetic antivenoms and new venom-neutralizing technologies, to improve effectiveness, safety, and availability.

Recent advancements in neutralizing deadly snake toxins.

1) AI-designed proteins shown to neutralise snake venom toxins

Researchers have harnessed artificial intelligence to develop innovative proteins capable of neutralizing deadly snake venom toxins. The study, led by Nobel Laureate David Baker from the University of Washington and Timothy Patrick Jenkins of the Technical University of Denmark, utilized deep learning techniques to engineer proteins that effectively bind to and neutralize cobra venom toxins. These AI-designed molecules successfully protected mice from lethal doses of ‘three-finger toxins,’ with survival rates ranging from 80% to 100%, depending on the dosage and protein variant. This cutting-edge method presents a promising alternative to conventional antivenoms, which are typically derived from animal plasma and may be expensive, less effective, and linked to side effects. The AI-generated proteins are simpler to manufacture and could improve access to snakebite treatments, particularly in developing regions.↗

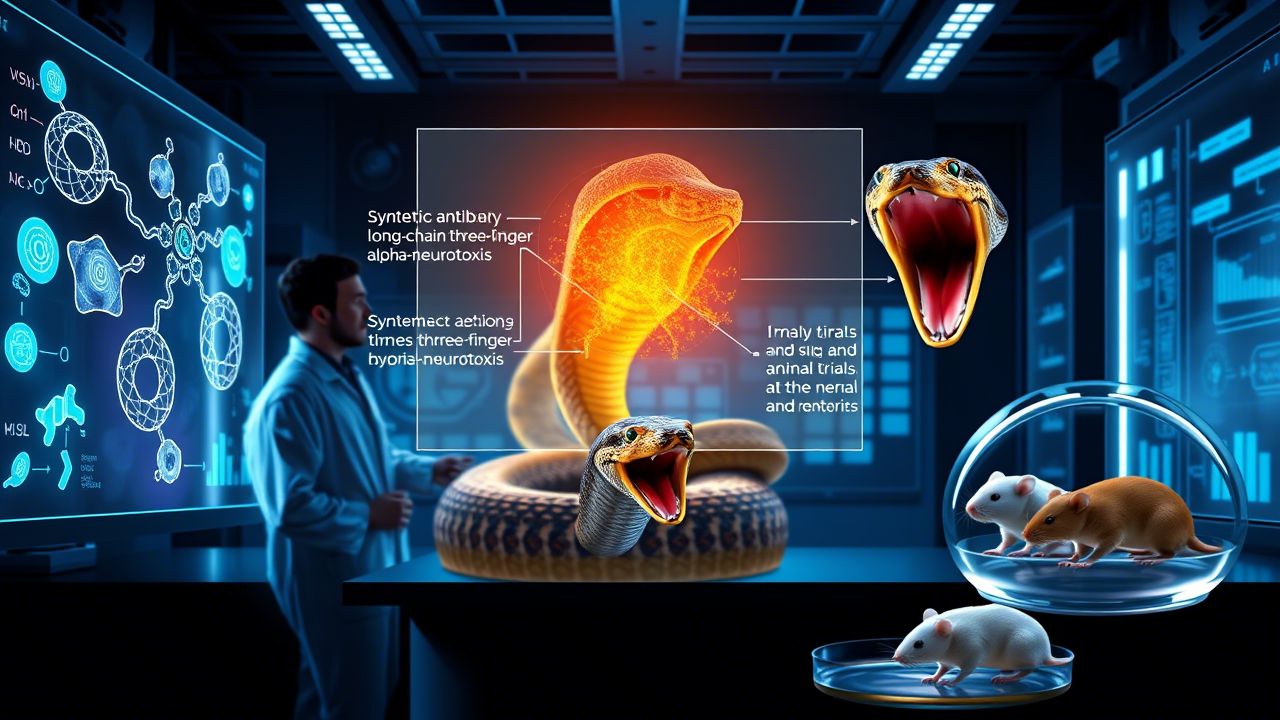

2) Development of Synthetic Antibodies Against Snake Venom

A major breakthrough in snakebite treatment is the development of a synthetic antibody designed to neutralize the deadly venom of Elapidae family snakes, including black mambas, king cobras, and kraits. Scientists screened around 60 billion artificial human antibodies to find those capable of effectively counteracting long-chain three-finger alpha-neurotoxins, the primary toxic component in these snakes’ venom. In animal trials, the selected antibody provided complete protection to mice against lethal doses, even when administered up to 20 minutes after envenomation. This innovation paves the way for a universal antivenom that could combat venom from multiple snake species globally, potentially revolutionizing snakebite treatment.↗

3) AI Application for Snake Identification in South Sudan

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is piloting an AI-driven application in South Sudan to improve snakebite treatment by accurately identifying venomous snake species. The AI system, trained on a vast dataset of 380,000 snake images, assists medical professionals in selecting the most effective and appropriate antivenom, optimizing the use of these rare and expensive treatments. Early trials suggest that the AI can sometimes surpass human experts in species identification, reducing misdiagnoses and improving patient care. Given the high prevalence of snakebites in the region where access to proper treatment is often limited this technology could significantly decrease fatalities and complications. Additionally, by minimizing antivenom waste and ensuring timely intervention, the AI tool has the potential to revolutionize snakebite management in resource limited settings.↗

Advancements in Healthcare:Exploring the Scope, Timeline, and Impact

Recent advancements in healthcare technologies are transforming snakebite treatment. These innovations not only provide more effective therapeutic solutions but also pave the way for broader applications in toxin neutralization and emergency medicine. Let’s examine these developments through the lens of their scope, timeline, and impact on snakebite treatment.

Scope of Innovations

The field of snakebite treatment has witnessed groundbreaking progress in areas such as synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence (AI). Key innovations include:

The field of snakebite treatment has seen remarkable advancements across multiple domains, including synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence (AI). Some of the most significant breakthroughs include:

- Synthetic Antivenoms :

Synthetic antivenoms represent a paradigm shift from traditional animal-derived therapies. These lab engineered molecules mimic antibodies and can target a wide range of venom toxins simultaneously, offering a universal solution to snakebites.↗

- Nanoparticle Based Therapies :

Nanoparticles act as molecular scavengers, binding to venom components and neutralizing them before they cause harm. This technology is particularly promising due to its ability to work across different venom types.↗

- Recombinant Proteins via Gene Editing :

Using CRISPR and other gene editing tools, scientists have developed recombinant proteins that can be mass-produced in bacteria or yeast. These proteins are designed to specifically counteract venom toxins.↗

- Plant-Based Solutions :

Molecular pharming using genetically modified plants to produce antivenom components offers a sustainable and scalable alternative to traditional production methods.↗

- Portable Diagnostic Kits :

Advances in AI and biosensors have led to the development of portable diagnostic kits capable of identifying venom type and severity within minutes, enabling faster and more accurate treatment.↗

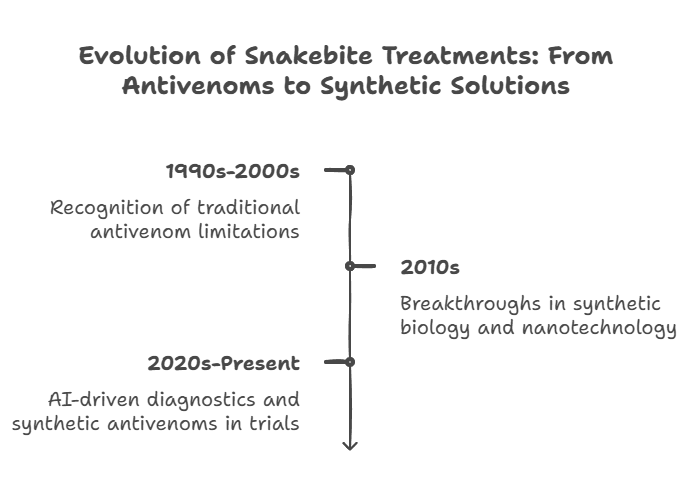

Timeline of Advancements

The development of improved snakebite treatments has progressed significantly over the last few decades:

- 1990s-2000s – Traditional antivenoms remained the gold standard, but researchers began recognizing their limitations, including allergic reactions and species specificity.

- 2010s – Early breakthroughs in synthetic biology and nanotechnology laid the foundation for alternative antivenom solutions. Scientists developed nanoparticle-based therapies and synthetic antibodies with enhanced stability and broader effectiveness.

- 2020s-Present – Advancements in AI-driven diagnostics, synthetic antivenoms, and nanotechnology-based treatments have accelerated, with several reaching clinical trial phases. Some promising synthetic antivenoms are undergoing regulatory approvals and could soon replace conventional options

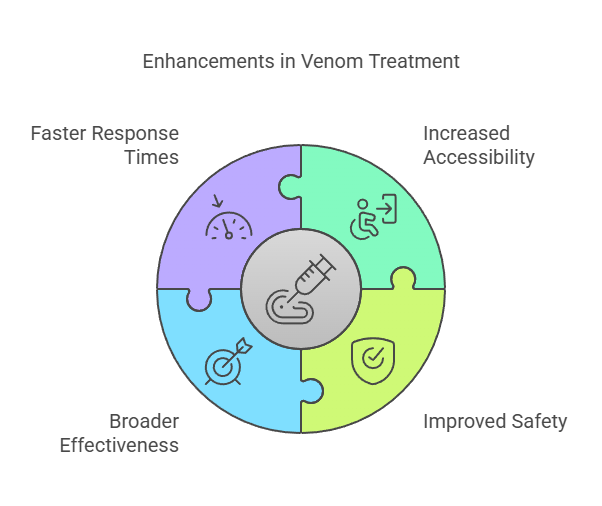

Impact on Snakebite Treatment

These innovations have the potential to transform how snakebites are treated worldwide:

- Increased Accessibility – Synthetic antivenoms and nanoparticle treatments eliminate the reliance on animal-derived antibodies, making production cheaper and more scalable.

- Improved Safety – Reducing the risk of allergic reactions and serum sickness makes treatments safer for a larger population.

- Broader Effectiveness – New therapies can target multiple venom types, reducing the need for species-specific identification before treatment.

- Faster Response Times – AI-assisted diagnostics and faster-acting therapies improve survival rates, particularly in remote or resource-limited regions.

These groundbreaking treatments mark a major shift in healthcare, offering faster, safer, and more accessible solutions for snakebite victims worldwide.

Challenges Ahead

Despite these groundbreaking innovations, there are still hurdles to overcome. Regulatory approval processes for new therapies can be lengthy, and funding for snakebite research remains limited compared to other global health priorities. Additionally, ensuring equitable access to these treatments in low-income countries will require international collaboration and investment.

Conclusion

Neutralizing deadly snake toxins is a multifaceted challenge that demands creative solutions. From synthetic antivenoms and nanoparticles to plant-based production systems, the future of snakebite treatment looks promising. As science continues to advance, we move closer to a world where no one has to fear the bite of a venomous snake.

By supporting research initiatives and advocating for increased awareness, we can help turn these scientific breakthroughs into life-saving realities. Together, we can make snakebites a preventable tragedy rather than an inevitable danger.